Bill Hayton produced a narrative that describes China as a domestic political creation, utilizing what he describes as a collection of stories that show: “A careful sifting of the evidence reveals that these ‘sacred’ boundaries are largely twentieth century innovations dreamed up by nationalist imaginations.”[1] Unfortunately, to produce these ‘stories’ there was a sifting of materials to produce a spectre of Western perceptions more suitable for the rhetoric of an extreme political rally, rather than a measured academic approach. The book accuses reformers and revolutionaries like Kang Yuwei and Sun Wen of adopting foreign ideas to invent a new vision of China, to do so it claims as factual a variety of events in isolation, and often states the details of those events incorrectly.

Kidnapped in London by Sun Yat-sen

A few examples, taken from the chapters relating to the formation of Chinese revolutionary thought and the South China Sea exhibit this pattern. Sun Wen (Sun Yat-sen) was kidnapped by the Chinese Legation in London, and according to Hayton: “[Dr James] Cantile then obtained a writ of habeas corpus from the High Court, obliging the legation to free Sun. Magna Carta, in effect, saved Sun’s life.”[2] There are two issues with this claim, the first is that Justice R. S. Wright, in the High Court of Justice, Queen's Bench Division, in the Matter of an Application for a Writ of Habeas Corpus decided: “I hesitate to make any order in this matter...partly because I doubt the propriety of making any order or granting any summons against a foreign Legation.”[3] Secondly, Metropolitan Police Superintendent, Donald Swanson, was of a similar mind to the learned Judge: “This is not a criminal matter, for neither the Chinese Ambassador, nor any of his suite, are under British Law. If anything, it is a gross breach of international relations.”[4] Sun Wen, in his book Kidnapped in London, relates the same information as above, and states that it was the Foreign Office that enabled him to be released, not the enforcement of a Bench issued Writ.[5] Why does Hayton rely on a secondary work in which the author Patrick Anderson notes: “After seven years’ archival research, I have been able to identify only one significant omission and/or deliberate truth in Sun Yatsen’s own first published account of this event in his life.”[6] Patrick Anderson goes on to cite the Foreign Office file that encloses the primary source materials quoted here, which any engaged reader would have recognised and accessed for themselves as a digital file; it is available from The National Archive at Kew to download and view. Finally, on the pages of Anderson’s book that are cited by Hayton, there is no mention of the Writ being granted as Hayton claims. For a work that claims to be based on a careful sifting of evidence, the central political figurehead in China’s Revolution and formation after the fall of the Qing should be better researched.

In the ‘story’ concerning the South China Sea the same lack of detail is apparent.

On a variation of a theme from his 2014 book, The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia, it is stated:

The Qing navy barely existed in the 1900s. The results of two decades of ‘self-strengthening’ policies, intended to create dockyards, skilled technicians, and modern maritime forces...were literally sunk, or captured, during the 1894/5 war with Japan...The surviving ships were too small to do more than patrol rivers or the immediate coastline.[7]

In his 2014 work, the claim was made: China didn’t possess another naval ship capable of reaching the islands of the South China Sea until it was given one by the United States 500 years later [in 1946].”[8] The reader is therefore supposed to believe that China didn’t have any naval vessels capable of sailing approximately 850 nautical miles to the loss of the 7,144 ton German built ships Ding Yuan and Zhen Yuan in 1895 was a seamless passage from zero possession of any ships, to their sinking in 1895, when they supposedly didn’t exist at all. This acceptance is supposed to take place without recognising the 1890 visits of the Beiyang Fleet to Singapore, Malaysia, and the Java Sea.[9] The contradictions in these two works, and their possible rebuttal through modern secondary literature published 14 years prior; Richard Wright’s The Chinese Steam Navy, 1862-1945, a detailed and scholarly work that any respectable academic interested in Chinese self-strengthening and post 1840 maritime history would know intimately, makes it difficult to understand how the narrative that follows such claims in both of Hayton’s books can be taken seriously.

The Chinese Steam Navy by Wright, R. N. J.

The events that take place during 1909, when China is supposed to have accidently ‘discovered’ Japanese guano mining on Pratas Island is also one that is short on details that can change the reader’s perception. According to Hayton: “In the absence of a genuine navy, the Customs Service was given the task of investigating developments on Pratas.”[10] This is a development on the claim made regarding the 1894-1895 sinking of the Qing Navy by Japan noted earlier. However, as reported in The Japan Weekly Mail at the time, a Japanese eyewitness stated:

On the 1st of March last a Chinese warship made its appearance off the Island. An officer landed, accompanied by an Englishman and one or two sailors, and on being asked what their business was, replied that they had no special business but had merely called at the place en route for Manila. Ten days later, however, the same vessel returned, accompanied by another, and on this occasion a larger party landed, including three foreigners... The Chinese officer than asked what had become of the shrine which originally stood on the island.[11]

Due to the use of ethnicity in describing an Englishman, and three foreigners, the Chinese officer and another accompanied by an Englishman, shows there was Chinese oversight and investigation. The description of two Chinese warships should also be noted, which, in combination, contradicts the description given by Hayton. Additionally, there is a mention of Admiral Li Zhun’s search for records in the archives: “We searched old Chinese maps, books, and the Guangdong Provincial Gazetteer and could not find such a name [Pratas].”[12] This raises a question, due to the inserted name Pratas by Hayton; why would a Chinese Naval Officer look in Chinese archives for the name Pratas, instead of Dongsha, which was recorded by the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs as the name used by Chinese fishermen, and planned to be lit with a lighthouse as early as 1870, as it was considered to be: “The only real danger of the Chinese Seas.”[13] There was no reason for a Chinese Officer to look for the name Pratas in Chinese records, unless he was looking in the Chinese Imperial Customs archives, when he would also have found the name Dongsha.

Then Guangdong Fleet Admiral Li Zhun

The narrative concerning the Paracel Islands, Xisha in Chinese is also problematic. Hayton claims:

Li’s forces didn’t have the ability to sail that far [to the Paracels] so, once again, the Custom’s cruiser Kaiban transported three of the governor-general’s officials to the islands.... The interest in these rare creatures [sea turtles] and general atmosphere of surprise demonstrate how little Chinese officials and the general public knew about the islands before 1909.

Another search of local archives and an inquiry to the Statistical Department of the Chinese Imperial Customs would have shown the folly of this statement. During November 1882, the S.S. Paladin, 1,375 tons, sailing with 55 passengers and crew from Saigon for Hong Kong, was rescued by Commander Wei Zheng Sheng,韋振聲, of the Chinese Naval Gunboat Sui Jing 绥靖 (Pacification), off the Paracel Island Ya Zhou 崖州, Wan Li Chang Sha 萬里長沙, for which he received promotion and cash rewards distributed by order of the Emperor; another event involving a Chinese naval ship and personnel that was widely reported in Britain at the time of the incident.[14] It is therefore difficult to know how a claim could be made that supports lack of navigational knowledge of the Paracels by Chinese naval officers prior to 1909, as the above example exhibits.

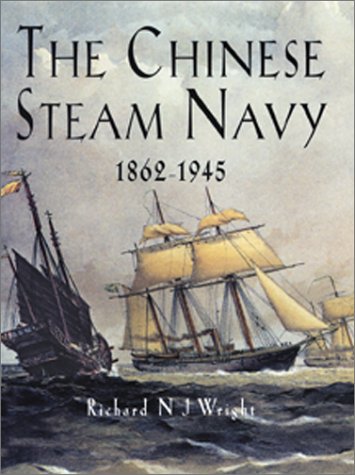

There is final point concerning the existence of a modern Chinese Navy after 1895. While it is claimed that China didn’t have a navy in 1909, after the events of 1895, this is not correct. China took delivery of the Vulcan built torpedo gunboats Fei Ting, 850 tons, and Fei Ying, 350 tons, the Vulcan built steel cruisers Hai Yung, Hai Chou, and Hai Chen, all of 2,950 tons, two Armstrong Elswick built cruisers Hai Chi and Hai Tien, 4,300 tons, and the Mawei Shipyard (Fuzhou, Fujian) built 1,900 steel cruiser Tung Chi, with the torpedo gunboats Chien Wei and Chien An of 871 tons.[15] All of these ships were in service during 1909, along with another 80 odd vessels on the list, the Hai Chi returning to Britain with 43 Chinese Officers on board for the 1911 Spithead Naval Review as widely reported in Britain: “The first of the foreign warships attending the Coronation Review at Spithead to cast anchor in British waters is the Chinese cruiser Hai-Chi, 4,300 tons, from Shanghai, which place she left on April 21st.”[16] As she sailed for New York after the Review, arriving on the 10th of September, then, after Rear-Admiral Cheng visited President Taft, heading via Charleston to Cuba, and Bermuda before returning to Britain and then sailing to China via Singapore, it is difficult to understand why the perception that is presented can be acceptable.[17] China had a navy in 1909, despite the claims made in two pieces of work published by Hayton, one that had ships capable of sailing via the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic Ocean to Britain, without the presence of foreign advisors.

Chinese cruiser Hai Chi in New York City, September 1911

There is another point of a political nature concerning 1909 in particular, which had created issues for China since 1905, the year Japan was victorious against Tsarist Russia. It should be remembered that this period was when Japanese political agitation in China over an extension of railway rights it had received from Russia, particularly the Antung-Mukden (Dandong-Shenyang) line extension, was at its height.[18] It was not a simple issue to be dealt with in isolation, it was part of a complex national security situation involving Sino-Japanese affairs after Japan’s two victories in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), which had placed Japan in a dominant position near the Manchu homelands when she built The South Manchurian Railway.[19] As a result of the war with Russia and her post war activity, Japan gained access to the oil rich coal shale mines near the future Daquin Oil reserve, and the point where on 18th September 1931 the Mukden Incident was initiated, beginning which is known in China as the 14 Year War Of Resistance Against Japan.[20]

In conclusion, it is difficult to recommend this book to even the casual reader. This is due to its many flaws, and lack of the claimed: “Careful sifting of the evidence.”[21] It appears that evidence was sifted and picked through to support a political opinion, rather than a careful academic examination of China’s history, which remains solely needed. The reader may ask how this writer is aware of a different narrative, to which the response is all the materials utilised above, other than a few primary sources not available there, were from the same School of Oriental and African Studies library apparently utilised by Bill Hayton in the research for this book.[22] As a work that claims a certain path for China in its very last paragraph based on memories of the 1930’s that would be of major interest to politicians and others, it deserves to be better researched.