On April 6, 2020, Morgan Ortagus, spokesperson of the United States Department of State made a statement on the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel in a collision with a China Coast Guard ship, saying that “the PRC’s sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel” is “the latest in a long string of PRC actions to assert unlawful maritime claims and disadvantage its Southeast Asian neighbors in the South China Sea.” In fact, this is not the first time that the Trump administration blasts Beijing for its claims in the South China Sea as “unlawful maritime claims.” As far back as July 2019, the U.S. Department of State made clear its opposition to China’s “unlawful maritime claims” in the South China Sea. This kind of public labelling implies that the stance of Washington on the South China Sea issue has changed once again.

I. Basic Stance of Washington on the South China Sea Issue after the Cold War

In May 1995, the U.S. Department of State issued the U.S. Policy on Spratly Islands and South China Sea immediately after the “Mischief Reef Incident”, through which the US for the first time unveiled its policy toward the South China Sea disputes, clarified its maritime interests, and made clear the principles, rules and norms it endorsed and upheld for solving the South China Sea disputes and managing the regional situation. The policy statement articulated five key points:

(1) The US takes no position on the legal merits of the competing claims to sovereignty over the various islands, reefs, atolls, and cays in the South China Sea;

(2) The US supports peaceful resolution of disputes in the South China Sea through diplomatic processes and welcomes the 1992 ASEAN Declaration on the South China Sea;

(3) The US seeks to maintain freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea;

(4) The US is opposed to any maritime claim or restriction on maritime activity in the South China Sea that is not consistent with the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the UNCLOS); and

(5) The US opposes unilateral action to escalate the tensions and the use or threat of force to resolve competing claims. This policy statement has since become the basic stance of Washington on the waters for years.

This statement actually reiterated the U.S. “neutrality” over the South China Sea disputes, and articulated its four fundamental maritime interests, namely peaceful resolution of disputes through diplomatic negotiations, maintaining the freedom of navigation and overflight, the smooth running of commercial activities, and the respect for international law. In the meantime, given its own interests, even though Washington did not interfere with the South China Sea disputes, it expressed concerns about the way of all claimants to advance their claims.

II. Changes of Stance under the Obama Administration

The Obama administration made great changes to the U.S. stance on the South China Sea issue progressively to meet specific objectives at each stage. A review of statements on its stance outlines a full picture of Washington’s logic underpinning its policy changes regarding the South China Sea. Generally, the changes were made in the following stages.

1. The Revision of “Neutrality”: Explanations and Supplements (2009-2010)

“The USNS Impeccable Incident” in 2009 set Washington off to consider readjusting its policy toward the South China Sea. This incident intensified China-U.S. divergence over the connotations of freedom of navigation in exclusive economic zones (EEZ), and aroused Washington’s concerns about China’s strategic intentions and regional prospects. As the strategic focus of Washington gradually shifted to the Asia-Pacific region, the U.S. Department of State and the Department of Defense started to modify its policy toward the South China Sea (See Table 1). In July 2009, Scot Marciel, then Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, expounded on the new administration’s policy leanings in the South China Sea and explained the new connotations of Washington’s “neutrality”:

“U.S. policy continues to be that we do not take sides on the competing legal claims over territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea. In other words, we do not take sides on the claims to sovereignty over the islands and other land features in the South China Sea, or the maritime zones (such as territorial seas) that derive from those land features. We do, however, have concerns about claims to “territorial waters” or any maritime zone that does not derive from a land territory. Such maritime claims are not consistent with international law, as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention.”

In fact, Washington narrowed the scope of “neutrality” set forth in the 1995 policy statement down from taking no position on the legal merits of the competing claims of claimants to taking no position on the sovereignty over various islands and reefs, but started to take a clear position on the maritime claims of all claimants. According to the U.S., this is due to:

“The assertions of a number of claimants to South China Sea territory raise important and sometimes troubling questions for the international community regarding access to sea-lanes and marine resources. There is considerable ambiguity in China’s claim to the South China Sea, both in terms of the exact boundaries of its claim and whether it is an assertion of territorial waters over the entire body of water, or only over its land features. In the past, this ambiguity has had little impact on U.S. interests. It has become a concern, however, with regard to the pressure on our energy firms, as some of the offshore blocks that have been subject to Chinese complaint do not appear to lie within China’s claim. It might be helpful to all parties if China provided greater clarity on the substance of its claims.”

In addition, Washington for the first time labeled China’s claims to oil and gas resources in the South China Sea as “intimation and coercion”, and supported all claimant states to refrain from escalating and complicating disputes under the framework of Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (hereinafter referred to as the DoC) concluded in 2002.

Table 1 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2009-2010)

In July 2010, Hillary Clinton officially announced the policy of the Obama administration on the South China Sea in her speech delivered at the 17th ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). She reaffirmed the fundamental interests and principles of the United States as stated in 1995 and announced to adjust its policy as follows:

(1) The US supports a collaborative diplomatic process by all claimants for resolving the various territorial disputes without coercion ,and opposes the use or threat of force by any claimant;

(2) The US starts to take a clear position on legal merits of the maritime claims of all claimants;

(3) The US encourages the parties to reach agreement on a full code of conduct and maintain the status quo;

(4) Respect for the interests of the international community and responsible efforts to address these unresolved claims and help create the conditions for resolution of the disputes and a lowering of regional tensions;

(5) To ensure its policy credibility, the U.S promises to give strong bipartisan support, and one of diplomatic priorities over the course to secure its ratification in the Senate.

Officials from the U.S. Department of Defense expressed a similar stance on occasions like the Shangri-La Dialogue.

During this period, the US managed to “legitimize” its interference in the South China Sea disputes by renewing the connotations of its “neutrality” over relevant issues. New explanations and supplements to its interests, principles and conduct standards of all claimants were also unveiled.

2. The Demand on All Claimants to “Clarify” Claims: Increased Pertinence (2011-2013)

As the US deepened its interference in the South China Sea issue, it began to reinforce the inclination and pertinence of its stance (See Table 2).

Table 2 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2011-2013)

In July 2011, Hillary issued two statements on the South China Sea and related sovereignty issue in a row to articulate adjustments to the U.S. stance:

First, the US sought to intervene in the multilateral negotiations over a “Code of Conduct” (COC) by alleging that the situation of the South China Sea concerned its regional interests, hoping for formulating conduct standards of all South China Sea claimant states. From 2010 onward, ASEAN member states have begun to push for COC negotiations, and Hillary expressed support for the endeavor as well as Washington’s intention to play a role in the process through her speech given in Hanoi, Vietnam. In June 2011, Hillary reaffirmed the stance in a conversation with Albert del Rosario, former Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines. One month later, in a talk with Marty Natalegawa, former Foreign Minister of Indonesia, she went on to clarify that:

“So, we think that it was an important first step, but only a first step in adopting the Declaration of Conduct. And we commend, again, Indonesia's leadership in achieving that, and urge that ASEAN move quickly -- I would even add urgently -- to achieve a code of conduct that will avoid any problems in the vital sea lanes and territorial waters of the South China Sea.”

At the same time, Washington blasted Beijing for its activities in the South China Sea as de-stabilizing actions ought to be bound by COC:

“We are concerned by the increase in tensions in the South China Sea and are monitoring the situation closely. Recent developments include an uptick in confrontational rhetoric, disagreements over resource exploitation, coercive economic actions, and the incidents around the Scarborough Reef, including the use of barriers to deny access. In particular, China's upgrading of the administrative level of Sansha City and establishment of a new military garrison there covering disputed areas of the South China Sea run counter to collaborative diplomatic efforts to resolve differences and risk further escalating tensions in the region.”

Second, the Obama administration in its policy statements urged all claimants to “clarify” their claims and legal merits in the South China Sea since 2011. It was intent on making the UNCLOS the only legitimate source for “clarifications” of all claimants:

“In order to decrease the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation, we continue to urge all parties to clarify and pursue their territorial and maritime claims in terms consistent with international law, including the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention.”

To that end, the US laid greater emphasis on the importance of joining the UNCLOS in maintaining its interests in the South China Sea:

“For our part, we can strengthen our hand in engaging disputes in the South China Sea by joining the Law of the Sea Convention. As the Secretary emphasized when she testified before the full Committee in May. ... Our navigational rights and our ability to challenge other countries’ behavior should stand on the firmest and most persuasive legal footing available, including in critical areas such as the South China Sea. ... As a party to the convention, we would have greater credibility in invoking the convention’s rules and a greater ability to enforce them.”

It also encouraged all claimants to advance “clarifications” of their respective claims by international arbitration or other means:

“We continue to urge all parties to clarify and pursue their territorial and maritime claims in accordance with international law, including the Law of the Sea Convention. We believe that claimants should explore every diplomatic or other peaceful avenue for resolution, including the use of arbitration or other international legal mechanisms as needed. We also encourage relevant parties to explore new cooperative arrangements for managing the responsible exploitation of resources in the South China Sea.”

The US toiled to establish connections between the COC and the “clarifications” of all claimants, asserting that such “clarifications” could contribute to the conclusion of COC as soon as possible:

“And the United States takes no position on any claim made by any party to any disputed area. What we want to see is a resolution process that will be aided by the code of conduct that ASEAN is working toward, based on the Declaration of Conduct, and that the principles of international law will govern, so that there can be peaceful resolution of all the claims. In order to achieve that, every claimant must make their claim publicly and specifically known, so that we know where there is any dispute. And secondly, all claims must be related to territorial characteristics.”

During this period, the US technically made its way into the South China Sea issue, and targeted China’s maritime claims and activities without public confrontation. It is worth noting that Washington’s stance was still based on some truth, even though its purpose of targeting China’s claims and activities gradually came to light. For example, in hot regional issues like the Scarborough Shoal Incident, the Obama administration did not burn the boat by recklessly responding to the Philippines’s request for U.S. military intervention. On top of that, the U.S. Department of State and the military took concrete action to push the Congress to approve the UNCLOS, in a bid to boost the credibility of the administration’s policy.

3. Publicly Questioning and Challenging China’s “Nine-Dash Line” Claim (2014-2016)

During this period, the South China Sea issue became a serious concern of the U.S. Congress and the public. At the same time, to cooperate with the Philippines in the South China Sea Arbitration, the White House became more aggressive in its stance and started public charges against China (See Table 3).

Table 3 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2014-2016)

In February 2014, Daniel R. Russel, then Assistant Secretary of State openly questioned China’s “Nine-Dash Line” claim in a hearing before the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives. This was the first time that the US had denounced China in public for its South China Sea claims, indicating that Washington had turned back on “neutrality”:

“I think it is imperative that we be clear about what we mean when the United States says that we take no position on competing claims to sovereignty over disputed land features in the East China and South China Seas. First of all, we do take a strong position with regard to behavior in connection with any claims: we firmly oppose the use of intimidation, coercion or force to assert a territorial claim. Second, we do take a strong position that maritime claims must accord with customary international law. This means that all maritime claims must be derived from land features and otherwise comport with the international law of the sea. So while we are not siding with one claimant against another, we certainly believe that claims in the South China Sea that are not derived from land features are fundamentally flawed…China’s lack of clarity with regard to its South China Sea claims has created uncertainty, insecurity and instability in the region…Any use of the "nine dash line" by China to claim maritime rights not based on claimed land features would be inconsistent with international law”.

In March, the US expressed support for the case filed by the Philippines and encouraged other nations to follow suit:

“The United States reaffirms its support for the exercise of peaceful means to resolve maritime disputes without fear of any form of retaliation, including intimidation or coercion All countries should respect the right of any States Party, including the Republic of the Philippines, to avail themselves of the dispute resolution mechanisms provided for under the Law of the Sea Convention. We hope that this case serves to provide greater legal certainty and compliance with the international law of the sea.”

In December, the U.S. Department of State issued “Limits in the Seas” (No. 143)— China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea, before the deadline set by the temporary Arbitral Tribunal of the South China Sea Arbitration under the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague for China to submit its answer to the complaint. This report presented subjective assumptions and interpretations of China’s “Nine-Dash Line” claim. Part of these interpretations was also reflected in the final award. Though hard to determine whether there was any connection, the sequence was irrefutable.

In March 2015, Russel criticized China for its construction on some islands and reefs in a hearing before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations:

“Under international law it is clear that no amount of dredging or construction will alter or enhance the legal strength of a nation's territorial claims. No matter how much sand you pile on a reef in the South China Sea, you can’t manufacture sovereignty.”

Russel also defended the construction of other claimant states on some islands and reefs started even earlier than those of China:

“It is certainly true that other claimants have added reclaimed land, placed personnel, and conducted analogous civilian and even military activities from contested features. We have consistently called for a freeze on all such activity. But the scale of China’s reclamation vastly outstrips that of any other claimant. In little more than a year, China has dredged and now occupies nearly four times the total area of the other five claimants combined.”

Meanwhile, based on his partial understanding of the UNCLOS provisions, he judged on the jurisdiction of the temporary Arbitral Tribunal as well as the legal binding of its award:

“I would like to make two points regarding the Law of the Sea Convention. First, with respect to arbitration, although China has chosen not to participate in the case brought by the Philippines, the Law of the Sea Convention makes clear that “the absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings.” It is equally clear under the Convention that a decision by the tribunal in the case will be legally binding on both China and the Philippines.”

On July 12, 2016, the US voiced support for the arbitration award and urged China to “avoid provocative statements or actions”. The statement and document issued by the US corresponded with the key progress of the South China Sea Arbitration, jointly pressuring China’s claims in the South China Sea.

III. New Adjustment of the Trump Administration

Since Trump took office, China has been labeled as a “strategic competitor” through a series of documents including the National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy and etc. To serve the need of great-power competition with China. Trump administration’s stance toward the South China Sea issue has been even more aggressive without any basic equilibrium and neutrality.

1. Playing up “China Threat Theory” on the South China Sea: Piling on Threat Perception (2017-2018)

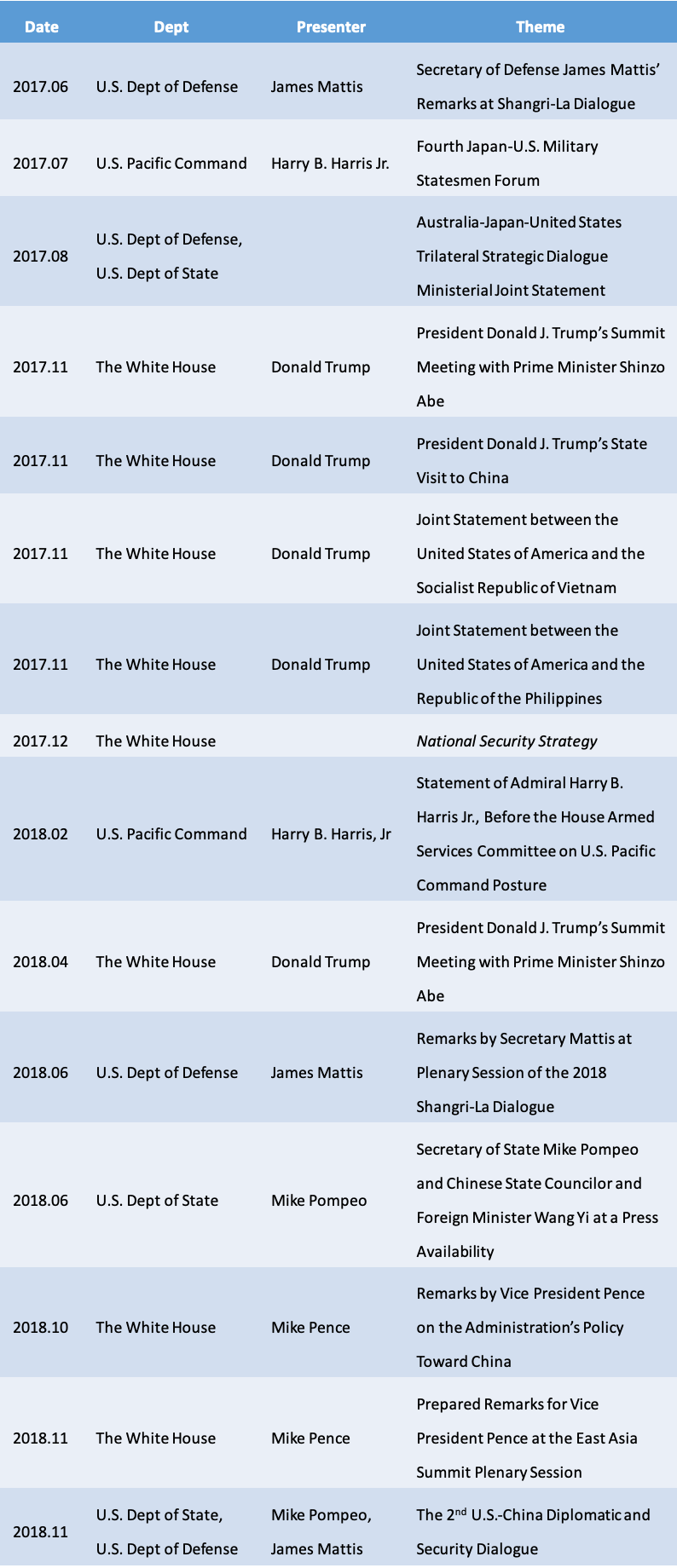

The US shifted the core of its stance on the South China Sea from safeguarding its own principles and interests to creating perceptions of a threatening China through discussions on the South China Sea issue. To argue for the “rationality” of taking China as a competitor, the US intentionally started with the South China Sea and relevant issues to irritate domestic hostility against China (See Table 4).

Table 4 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2017-2018)

On the Shangri-La Dialogue held in June 2017, then Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis noted four adverse effects of the artificial island construction of China, namely the nature of “militarization”, the “disregard” for international law, the “contempt” for other nations’ interests, and the efforts to dismiss non-adversarial resolution of issues. Following that in November, during Trump’s visit to China, he expressed concerns about "the militarization of outposts". In December, the newly-released National Security Strategy of United States indicated that China’s “militarization” of the South China Sea will “endanger the free flow of trade, threaten the sovereignty of other nations, and undermine regional stability,” and that China intends to "limit U.S. access to the region". This stance was basically followed by the White House, the U.S. Department of State and the military till end-2018. There were also some tougher remarks. For example on October 4, 2018, in his speech on the administration’s policy toward China, Vice President Mike Pence noted that China is constructing “an archipelago of military bases” and blamed it for displaying “aggression” against the US via the identification and verification of the U.S. warships in the South China Sea.

Generally, from 2017 to 2018, the stance of the US on the South China Sea issue were mainly about exaggerating and defaming China as “militarizing” or “actually controlling” the waters, so as to intensify the perception of China as a threat to all claimants and the world. Its policy toward the South China Sea has also gradually shifted from safeguarding national interests and upholding principles of international law to blatantly playing power politics amidst US-China competition.

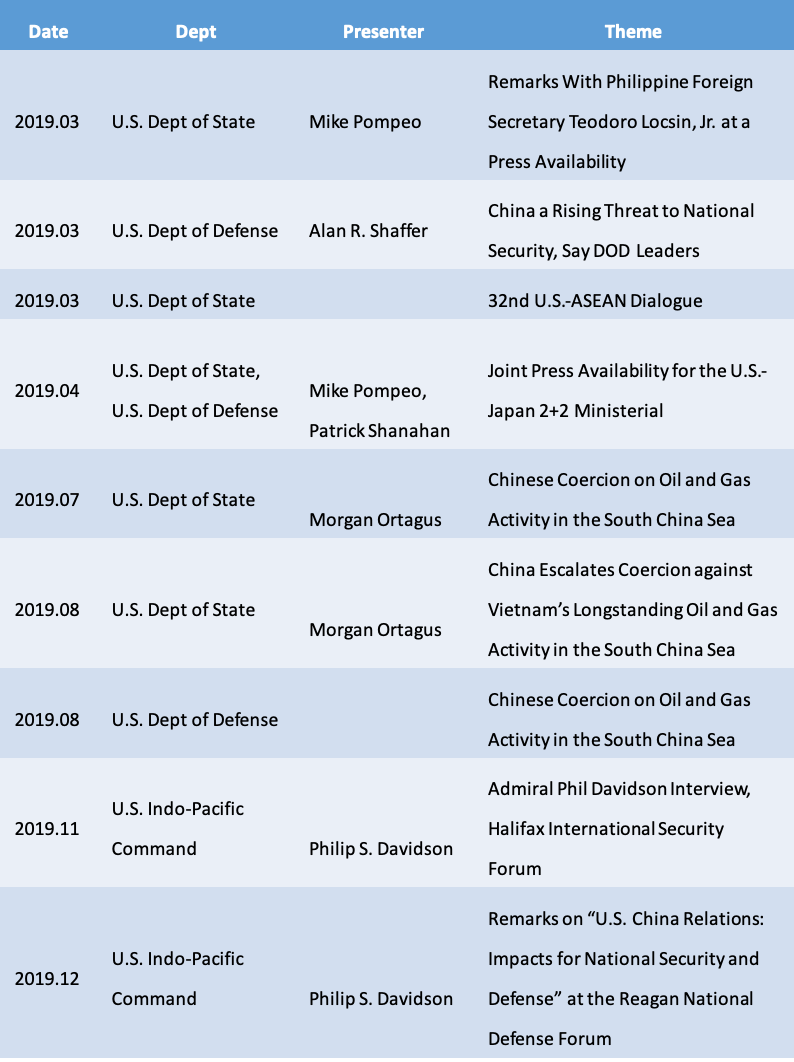

2. Fully against China on the South China Sea: Further Touting Threat Theory Regardless of Facts (2019)

Since 2019, aside from accusing China of “militarizing” the South China Sea as usual, the US started to charge and threaten China for its maritime claims and actions on more fronts (See Table 5).

Table 5 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2019)

In July 2019, in a statement released by the U.S. Department of State, the US for the first time stated China’s claims in the South China Sea as “unlawful maritime claims”, which marked another serious escalation after the US labeled China’s “Nine-Dash Line” claim as “an ambiguous claim” and then “an excessive claim.” It also criticized China for “preventing ASEAN members from accessing more than $2.5 trillion in recoverable energy reserves,” and thus “threatening regional energy security”:

“China’s actions undermine regional peace and security, impose economic costs on Southeast Asian states by blocking their access to an estimated $2.5 trillion in unexploited hydrocarbon resources, and demonstrate China’s disregard for the rights of countries to undertake economic activities in their EEZs, under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, which China ratified in 1996.”

The US also hyped about the threat of the Chinese “maritime militia”, asserting that China uses it to “intimidate, coerce, and threaten other nations”, and “undermine the peace and security of the region.” It also censured China for posing “growing pressure” on the other countries to “accept Code of Conduct provisions that seek to restrict their right to partner with third party companies or countries”, which “further reveal its intent to assert control over oil and gas resources in the South China Sea”.

3. U.S. Stance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Opposing Every Move of China (2020)

In order to shift its domestic discontent, and also out of concerns that China would take advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to expand its sphere of influence at this time, the U.S. government has resorted to “attacking as a means of defend”, sparing no efforts to make false accusations against China and opposing China in every incident possible, regardless of the facts (See Table 6).

Table 6 Main Documents of the U.S. Stance (2020)

The U.S. Department of State and the Department of Defense has made remarks apparently biased towards Vietnam on the sinking of a Vietnamese fishing vessel after colliding with a China Coast Guard ship. The US has accused China, and described the incident as “the latest in a long string of PRC actions to assert unlawful maritime claims and disadvantage its Southeast Asian neighbors in the South China Sea”, despite the fact that the incident happened only seven nautical miles away from Woody Island under the jurisdiction of Sansha City, China. This kind of attitude means that the US has already taken sides with Vietnam regarding sovereignty over the Paracel Islands, whereas China has never recognized any disputes over the islands.

As the pandemic becomes more rampant globally, including in the US, Washington has blasted Beijing for exploiting the pandemic to “expand unlawful claims” in the South China Sea.

“Since the outbreak of the global pandemic, Beijing has also announced new “research stations” on military bases it built on Fiery Cross Reef and Subi Reef, and landed special military aircraft on Fiery Cross Reef. The PRC has also continued to deploy maritime militia around the Spratly Islands. China’s Nine-Dashed Line was deemed an unlawful maritime claim by an arbitral tribunal convened under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention in July 2016, a position shared by the U.S. Government”.

While ignoring its own frequent muscle-flexing and various actions of other claimants in the South China Sea, the US has turned a blind eye to China’s initiatives on joining hands with the international community, including the US, to fight against the pandemic, and actively extending support to countries, including the claimants in the South China Sea, in their endeavor to combat the pandemic. The US stated that:

“We call on the PRC to remain focused on supporting international efforts to combat the global pandemic, and to stop exploiting the distraction or vulnerability of other states to expand its unlawful claims in the South China Sea.”

IV. Characteristics and Trends of Changes in U.S. Stance

In recent years, through gradual adjustments year by year and leap-forward development phase by phase, the US has completely changed and revised its policy, which paved the way for it to intensify competition with China by leveraging the South China Sea and relevant issues. The changes of its policy manifest the following characteristics and trends:

First, its stance has shifted from the “superficial neutrality” to “anti-China rhetoric”. The Obama administration stressed the so-called “neutrality” and emphasized that it “takes no position” on the South China Sea sovereignty issue, while commenting and challenging the various claims on maritime rights and interests advanced by all claimants. Nevertheless, the Trump administration publicly opposes all claims and actions of China in the South China Sea, and even “takes sides” in sovereignty issue.

Second, its policy has weakened significantly in logic and rationality. While taking great pains to comprehensively revise its South China Sea policy, the Obama administration still attached much attention to the logic and rationality of its policy conveyed in official statements, with basic respect for the facts of regional hotspot issues such as the “Scarborough Shoal Incident”. The policy was integrated and systematic with a clear narrative logic. On the contrary, when it comes to the Trump administration, its policy seems to have become chaotic and illogical with many contradicting expressions, lacking in systematic descriptions of the U.S. national interests and binding principles. In addition, the Trump administration often disregards the principles and rules of international law and overlooks facts or even fabricates information for its own purposes. In a manner of speaking, telling lies and confusing the public have almost become the “new normal” under his administration.

Third, the attitude toward regional stability has subtly changed. For a long time, the US has been taking the peaceful resolution of the South China Sea disputes as its policy goal in the region. But in recent years, the U.S. government deems regional peace as disadvantageous. Some high-ranking U.S. officials even publicly remarked that “China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States.” Previously, the US has repeatedly reaffirmed its support for China to reach “a legally binding Code of Conduct for the South China Sea” with ASEAN member states to ease regional tensions. Nevertheless, as the negotiations have made headway, the US starts to back off, worrying that the COC might help advance China’s influence. As a result, the supportive attitude has been turned into touting gloomy forecasts or even public opposition. What are the intentions of the US anyway? Does it expect China and ASEAN member states to reach consensus on a COC, and thus maintain a peaceful and stable South China Sea? Or is it against COC talks between them, because a peaceful South China Sea might endanger its national interests? The changes afford much food for thought.

Since the Obama administration, the US has gradually made some revisions to its stance on the South China Sea issue, and is now taking an increasingly tough position with greater hostility against China. From upholding principles and highlighting pertinence to “anti-China rhetoric”, the U.S. government has been much weaker in the professionalism, authenticity and persuasiveness of its diplomatic parlance. It has also become used to disregarding facts and fabricating information, which not only undermines with the endeavors of the two countries to make accurate judgement on the interests and purposes of each other and come to understandings, but hampers the maintenance of the U.S. leadership and respect for international morality as it advocates. Furthermore, as the US gradually incorporates more military strategies in its stance on the South China Sea, the importance of diplomatic approaches and international laws is waning. Also, the bottom line of avoiding military conflicts risks being broken. This kind of change would undoubtedly bring forth greater uncertainties to regional peace and stability.