The South China Sea arbitration ruling is like a Sirens’ Song that mesmerizes Filipinos with its beauty and promise, unleashing conflicting emotions and desires, and driving some to madness and violence.[1] The Philippines is ratcheting up its rhetoric and actions on the South China Sea, with increasingly strident statements, more frequent diplomatic protests, and more aggressive law enforcement measures. The Philippines has given the ruling a new level of significance, with Foreign Minister Manalo declaring on July 12, 2023.[2]

“The Award stands as a beacon whose guiding light serves all nations. It is a settled landmark and a definitive contribution to the progressive development of international law. It is ours as much as it is the world’s. Just as lighthouses aid vessels in navigating the seas, the Award will continue to illuminate the path for all who strive towards not just the peaceful resolution of disputes but also the maintenance of a rules-based international order.”

Has the Award truly resolved the South China Sea dispute between China and the Philippines? Have all states used the ruling to guide their respective state practices? Has the Award made an undeniable contribution to the development of international law? Has the Award made the geopolitical game between China and the United States in the South China Sea more intense? Has the ruling made pre-existing conflicts between the claimants more irreconcilable?

The Award is not a lighthouse that aids vessels in navigating the seas, but a SONG OF SIRENS that invites the Philippines to run aground on a lost voyage. The Award has not been a catalyst for consensus-building, it has instead led to further fragmentation of the interpretation and application of UNCLOS. The Award has grossly undermined the authority and credibility of UNCLOS's dispute settlement mechanism, leading to the over-expansion of non-institutional mechanisms such as Annex VII, while hollowing out permanent institutions such as ITLOS.[3] The Award has thrown up more roadblocks and uncertainties in the way of resolving the South China Sea dispute through legal means. It has undermined the trust and confidence in UNCLOS's dispute settlement mechanism, making it less effective and trustworthy.

First, the Award is inconclusive on the issue of historic titles in relation to the nine-dash line. The Philippines asserts that “the Award definitively settled the status of historic rights”. Even assuming, arguendo, that the Award is valid, it would only determine the validity of historic rights in respect of China's claim to exclusive rights to living and non-living resources as characterized by the Award. The Award did not and could not address the validity of China’s historic title to the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, the validity of China’s historic title to the waters in the South China Sea, nor the validity of China's historic title to the Nansha Islands as a whole. This is because these are subject matters which no tribunal established under the Convention could or could not deal with, either because they are outside the scope of the Law of the Sea Convention or because States Parties may declare them to be excluded in accordance with Article 298 of the Convention. As it is, even after the Award was issued, the Philippines continues to repeatedly claim territorial sovereignty over the Second Thomas Shoal as part of the so-called ‘Kalayaan Islands’, rather than simply as part of the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.[4]

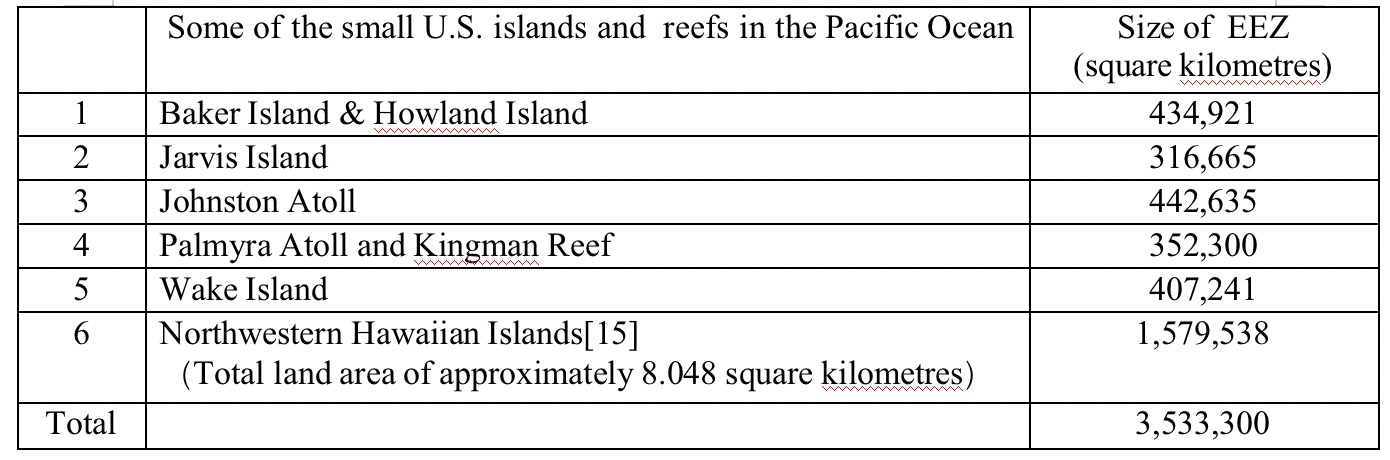

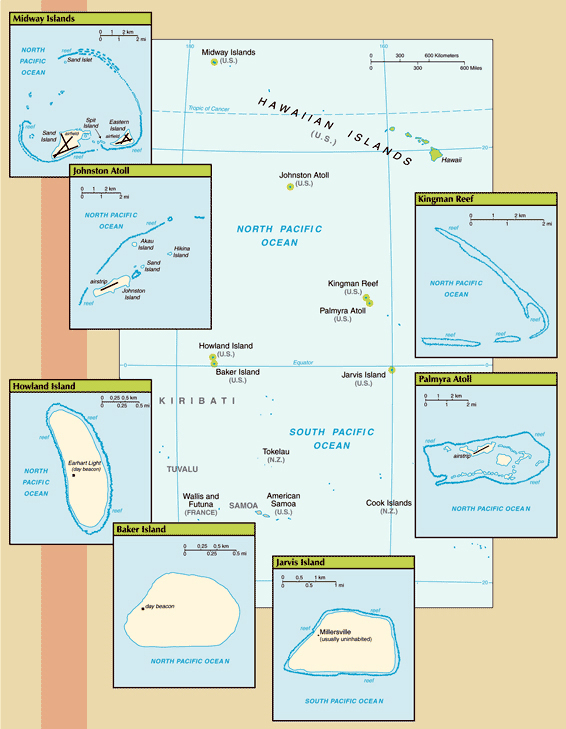

The Philippines claims that “the Award definitively settled maritime entitlements in the South China Sea”,[5] but this is precisely the most controversial part of the Award itself. The current practice of States that have claimed to be in favour of the Award, such as the United States, Japan, Australia, France and New Zealand, is almost invariably at odds with the Award.[6] Japan claims more than 400,000 square kilometres of exclusive economic zone and continental shelf on the basis of Okinotorishima, which has a total area of only 9.44 square metres, and Japan even claims more than 250,000 square kilometres of outer continental shelf based on Okinotorishima.[7] The United States claims a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone and continental shelf based on Kingman Reef, which is a tiny atoll with a land area of only 0.012 square kilometers.[8] France claims an exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of 434,619 square kilometres on the basis of Clipperton Island, and France also claims an outer continental shelf of Clipperton Island beyond 200 nautical miles.[9] Australia claims a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone and continental shelf based on Heard Island and the McDonald Islands, which are uninhabited due to their extreme natural environment.[10]

In contrast, China's Taiping Island, which has a land area of about 0.51 square kilometres, 54,000 times larger than Japan's Okinotori Reef and 42.5 times larger than the United States' Kingman Reef, is only entitled to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea under the ruling and cannot claim a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.[11] In practice, this applies not only to Kingman Reef but also to other uninhabited islands around which the United States has claimed a 200-nautical-mileexclusive economic zone, including at least Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Palmyra Atoll, Midway Atoll, Navassa Island and Wake Island. The natural environment of China's Taiping Island is significantly more favorable than that of most of these islands and reefs. It is clear that the United States has a double standard in defining islands and the maritime entitlements they can enjoy.[12]

Kingman Reef

The United States, a country that is already geographically privileged by its location on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, is not content with that, but also claims 200 nautical miles of maritime rights based on uninhabited small islands in the Pacific Ocean. The United States claims an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of proximate 3.53 million square kilometers based on six groups of uninhabited small islands in the Pacific Ocean.[13] This is larger than the entire size of the South China Sea. [14]

The statement by the Philippine Foreign Minister:“ In the decision to file a case for arbitration, the Philippines opted to take the path of principle, the rule of law and the peaceful settlement of disputes”.[16] The problem is that peaceful settlement of disputes does not exclude political negotiations, while legal means usually require the consent of the States involved. the Award contravenes the principle of state consent, misapprehends the compulsory dispute settlement procedures of the Convention, undermines the delicate balance between consent and compulsion, usurps the right of state’s parties to choose their own means of dispute settlement, and deviates from the basic purpose of international adjudication in the settlement and resolution of disputes.

The essence of the subject-matter of the arbitration is the territorial sovereignty over several maritime features in the South China Sea. Even if we assume that the subject matter of the arbitration was concerned with the interpretation or application of the Convention, that subject matter would still constitute an integral part of maritime delimitation between the two countries.[17] Therefore, it would fall within the scope of the declaration filed by China in 2006 in accordance with the Convention,[18] which excludes, among other things, disputes concerning maritime delimitation from compulsory arbitration and other compulsory dispute settlement procedures. In spite of the fact that the Arbitral Tribunal was fully aware that territorial issues do not fall within the scope of the Convention and that maritime delimitation disputes were excluded by China, the tribunal exceeded the scope of its mandate under the Convention, abused the principle of “the competence of the competence” set out in Article 288(4) of the Convention, and illegally established jurisdiction over a matter over which it clearly had no jurisdiction. This practice sets a dangerous precedent that jeopardizes the effectiveness of the dispute settlement mechanism under the Convention and violates the right of States parties to choose the means of peaceful dispute settlement of their own choice.[19] The competence-competence doctrine is not a blank check. It cannot be used to expand the jurisdiction of the dispute settlement mechanism beyond the limits set out in the Convention. It is not possible to adjudicate sovereignty issues under the guise of interpreting the Convention. Such legal maneuvers violate fundamental principles of international law and undermine the integrity of the Convention. In international arbitration practice, “ultra vires” is a common ground for challenging the validity of an Award.

The Award has failed to resolve the dispute between China and the Philippines, it has instead created more contradiction and disagreement. the Award has further polarized the debate over the South China Sea and has made it more difficult for China and the Philippines to reach a negotiated settlement. As M.C.W. Pinto has pointed out, the goal of any dispute settlement body is not to create a winner or a loser, but rather to provide a solution that is acceptable to both parties, so that they can use it as a basis for building friendly relations in the future.[20] Litigation is often seen as a “zero-sum game” in East Asian cultures, meaning that one party's victory necessarily means the other party's loss. This can lead to a breakdown in the relationship between the two parties, even if litigation brings so-called order. Traditional Chinese thinking has long emphasized the importance of avoiding litigation and preserving harmony.[21] Confucius said: “In hearing lawsuits, I am no better than anyone else. What we need is to have no lawsuits.”[22] The idea that "litigation is bad"(讼则终凶) and "harmony is precious"(和为贵) has a long history in China and continues to be influential today.[23] For example, the Chinese judiciary attaches significant importance to mediation and reconciliation between the parties involved, even advocating that "mediation should be given priority". Likewise, China's preference for settling international disputes through friendly consultation, rather than through legal proceedings, is rooted in its cultural values and its history. While international judicial institutions and systems are especially important, international adjudicatory bodies should also respect the traditional cultures and preferences of different regions and peoples, as well as their different choices in dispute resolution.

The Arbitral Tribunal failed to consider the complex cultural, historical, and geopolitical background of the South China Sea issue. The Tribunal treated the dispute between China and the Philippines with a simplistic and extreme view of the rule of law.The Tribunal interpreted the Convention in a radical and parochial manner, disregarding the broader context of the dispute. While nominally defending the rule of law, it has essentially shaken the foundations of the rule of law and created more division and conflict.[24]

Many people sympathize with the Philippines' dilemma as a relatively small and vulnerable nation that may face a dispute with a major power. However, there seems to be no need for the Philippines to deify itself and be moved by the act of filing an arbitration case. It is like Don Quixote tilting at windmills. China did not participating in the arbitration, after all. The Philippines is basically fighting for its own sense of honor and self-respect, but that is not going to be enough to resolve the dispute.

If it is only the “imagination” of certain individual politicians in the Philippines, it may not be so harmful. However, if it is fed to the Filipino people as a "stimulant", it may objectively aggravate the conflict between China and the Philippines and provoke confrontation between the two countries. Moreover, it is difficult to say that this is conducive to the peaceful resolution of disputes.

According to the statement by the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs, “the Award has reflected the rich maritime heritage of our country and our people, firm in the conviction that our rights over our maritime jurisdictions are indisputable”.[25] As noted above, the ruling itself is controversial and has not resolved the maritime disputes between China and the Philippines, it has not even brought the two countries closer to a basic consensus on the relevant maritime issues, but rather has widened the gap and made the political positions of the two countries even more irreconcilable. In a sense, the ruling has exacerbated the South China Sea dispute not only between China and the Philippines, but also between other claimant countries and China, and has planted a "landmine" that will be difficult to remove for the sake of the peace and stability of the region.

In fact, for all the littoral states around the South China Sea, none of them is a real winner. Not to mention whether the Philippines will really be able to achieve its goal of implementing the Award, and even if it does, it is likely to pay a heavy price for doing so. After all, if the nominal "winner" wants to implement the arbitral Award, the first and foremost thing it faces is a confrontation with China. If we must say there is a winner, the United States, a non-party, may be the only winner. The US used its “smart power” to help the Philippines launch the arbitration under the banner of upholding the “rules-based international order”. In addition to successfully separating China's relations with ASEAN countries, the US has also significantly expanded its legal basis for free navigation in the South China Sea, successfully tied other South China Sea claimants to its periphery for its ‘Indo-Pacific strategy’, and gained important weight in the geostrategic game with China. That is why, from the outset, China has viewed the arbitration as a "political provocation in the guise of law".[26] Its real purpose is not to resolve disputes but to help the United States contain China.

In conclusion, the Award itself is highly controversial, and the practice of even those states that claim to support it is contrary to the Award. It is a great illusion, and to some extent a self-deception, to equate the Award with international law or as part of it. the Award might never be indisputably part of international law. Nevertheless, the Philippine statement claims the legitimacy of the Award in a self-serving and self-reinforcing manner. To the extent that it has made the Award a totem and belief of the Philippine state and people, one cannot help but point out that this kind of extreme paranoia is dangerous. A rational and pragmatic country should be aware that the arbitral Award has not resolved the dispute. On the contrary, it has intensified the dispute and widened the differences in many respects, even making certain contradictions irreconcilable, with the danger of creating new conflicts and escalating old ones.

The Philippines has taken the controversial ruling as a golden opportunity to pursue unilateral gains, which is likely to inflame tensions and destabilize the South China Sea. This ruling is like the Sirens’ Song: it may sound sweet and alluring, but if we follow it blindly, we will be led to destruction. Any rational country should resist the temptation of the Sirens’ Song. Self-deception and self-righteousness may provide some sense of meaning and value, but no person or country can live on them alone.