In 2022, the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing by the Vietnamese fishing boats in the SCS continued to be prominent, intensifying the maritime fishery disputes between maritime law enforcement institutes of Malaysia and Indonesia and Vietnamese fishermen. AIS shows that Vietnamese fishermen operate an average of 7000 fishing vessels per month in 2022. The number of active Vietnamese fishing vessels are rising in the first quarter of 2023, to the scale of 9089 in April.

Source: SCSPI

Vietnam's Fishing Disputes with Indonesia

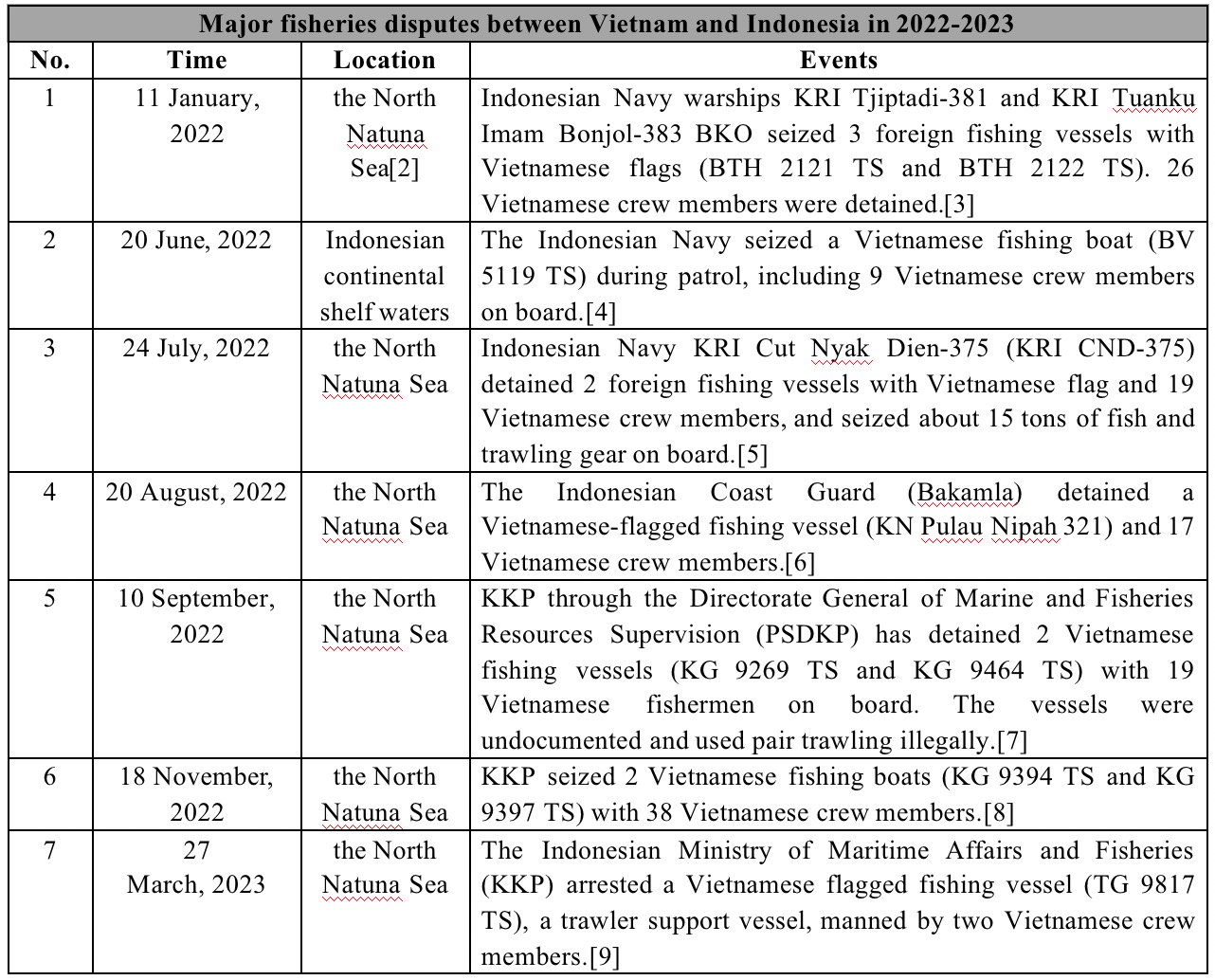

According to incomplete statistics, there were 6 fishery conflicts between Indonesia and Vietnam in 2022, 1 from January to April 2023. A total of 11 Vietnamese fishing boats and 128 Vietnamese fishermen were seized on the Indonesian side in 2022 (see table below for details). On July 18, 2022, the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (KKP), in cooperation with the Directorate General of Immigration and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, repatriated 17 Vietnamese crew members who were involved in illegal fishing.[1]

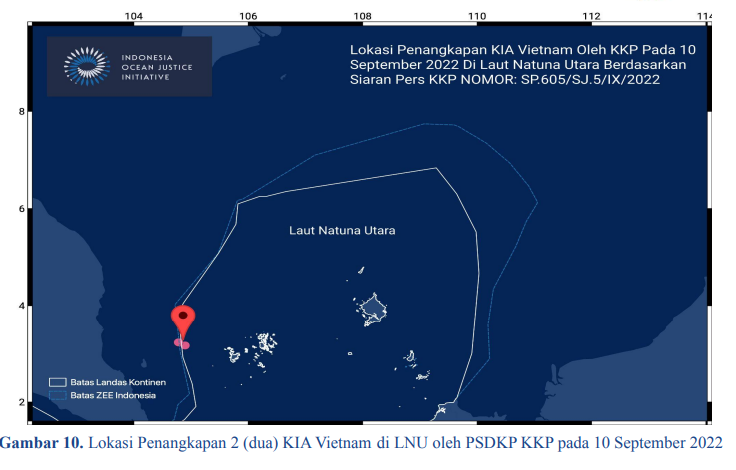

Location where Indonesia arrested two Vietnamese fishing boats on Sept. 10, 2022.

Source: Indonesia Ocean Justice initiative

Although a decreasing incidents of Indonesia seizing illegal Vietnamese fishing vessels or engaging in fishing disputes were reported in 2022 compared to previous years, this does not mean a decline in Vietnamese fishing incursions. There are still a large number of Vietnamese vessels illegally intruding into “Indonesian waters” to fish, raising concerns among local fishermen and environmentalists. For example, Indonesian fishermen in Natuna Islands complained to local authorities that they repeatedly encountered Vietnamese-flagged vessels fishing in the area, and alleged that the illegal Vietnamese fishing boats destroyed the local fishermen’s fishing grounds and greatly reduced their catch. Thus, Indonesian fishermen asked the Indonesian government to step up surveillance and security measures.

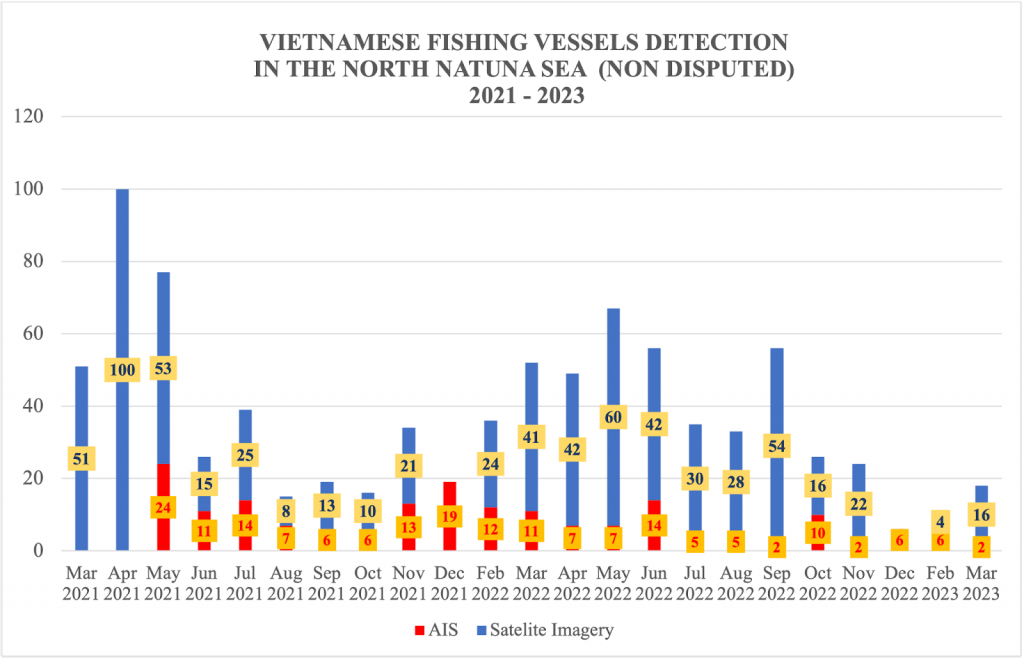

According to the Indonesian Ocean Justice Initiative (IOJI)’s report, 321 Vietnamese illegal fishing boats were monitored in Indonesian waters through AIS between February and September 2022. The number of Vietnamese fishing vessels topped in May, reaching 60 vessels. The actual number may be larger because some Vietnamese fishing vessels did not turn on the AIS signal while operating at sea.[10] In addition, IOJI said Vietnamese fishing boats usually operate in pair trawling, two boats sailing side by side and paralleling in the same direction, with the distance between 300 to400 meters. The use of some prohibited fishing gears causes systematic damage to the sustainable development of marine fishery resources.[11]

Number of Vietnamese fishing boats detected in Indonesia’s “undisputed” exclusive economic zone in 2021-2023

Source: Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative

In recent years, due to the constraints, such as the lack of patrol boats and budget, Indonesian maritime authorities’ patrol intensity and synergy have declined compared with before, which to a certain extent has led to Vietnam’s fishing encroachment activities to be more reckless. Therefore, on April 10, 2022, KKP stated that it would build two 50-meter-long fishery monitoring ships with “anti-illegal fishing” technology in 2022 to improve its ability combating illegal fishing.[12] Meanwhile, KKP submitted a proposal through the Directorate General of Marine and Fishery Resources Supervision (Ditjen PSDKP) to establish an intelligence network in the fisheries sector in the ASEAN region, hoping to strengthen deterrence and law enforcement to eradicate illegal fishing activities.[13]

Moreover, during Vietnamese President Nguyễn Xuân Phúc’s state visit to Indonesia from December 21 to 23, 2022, Indonesian President Joko Widodo expressed his hope that the two countries can reach agreements on aquaculture industry cooperation and combat IUU fishing as soon as possible. The two Presidents announced the completion of the 12-year process of Vietnam-Indonesia Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitation negotiations.[14] However, based on the current status, this does not seem to have eased the fishing tensions between Indonesia and Vietnam. On April 19, 2023, IOJI said this year’s movement patterns of Vietnamese fishing boats and Hanoi’s state-owned vessels in the North Natuna Sea showed little to no differences compared with the pre-EEZ period. The think-tank has tracked the movements since January.[15]

Vietnam's Fishing Disputes with Malaysia

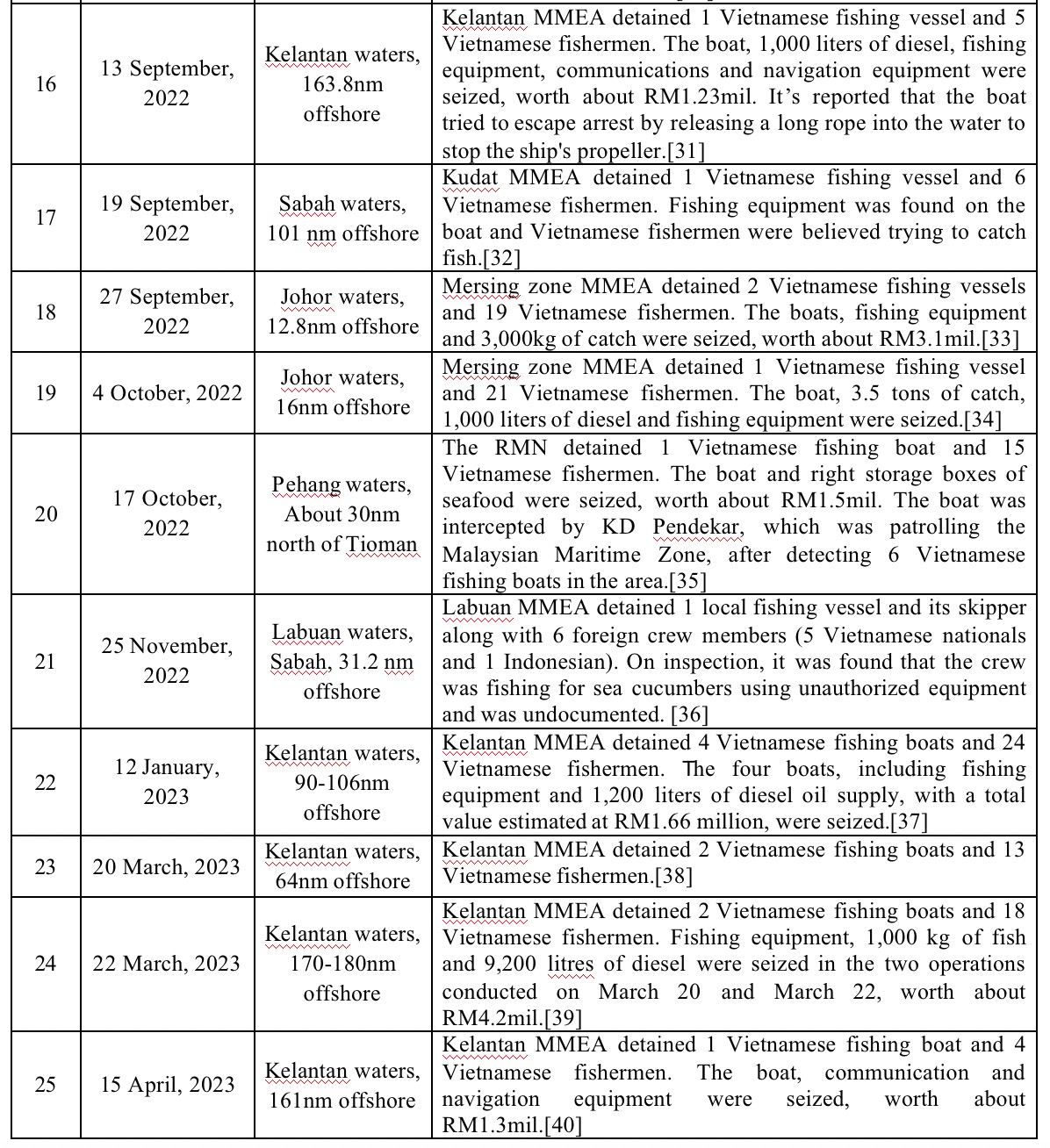

According to incomplete statistics, 21 events of fishing-relevant disputes were reported between Malaysia and Vietnam. Malaysia detained over 28 Vietnamese illegal fishing boats and over 300 Vietnamese fishermen in 2022, 4 occurred from January to April 2023 (see the table below).

Although Malaysia and Vietnam have set up a joint development zone in the disputed area east of the West Coast Malaysia and in the gulf of Thailand in 1992, rare proper arrangements were put up in place to resolve their fishing disputes. In April 2021, the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) and the Vietnam Coast Guard agreed to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU), aiming to “address the encroachment issue by Vietnamese fishermen, especially in the East Coast waters through information sharing such as using AIS.”[41] Up to the recent observation, however, Vietnamese fishermen’s trespassing fishing continues. According to a senior officer of MMEA, attempts to encroach on Malaysia’s water borders have increased drastically and alarmingly after Malaysia opened the country’s borders on 1 April. For example, Vietnamese fishermen caught fish near Tioman Island on the East Coast.[42]

In 2022, the fishery disputes between Malaysia and Vietnam on the frontline were generally under control and did not expand to other aspects of bilateral relations. There is no open confrontation between the maritime law enforcement forces of Vietnam and Malaysia, but frictions are inevitable in the process of law enforcement. For example, on June 11, Kudat MMEA encountered resistance when trying to arrest a Vietnamese fishing boat with 41 crews. The ensuing collision resulted in serious injuries to two Vietnamese fishermen.

Similar to the case in Indonesia, the recent COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the plight of MMEA’s shortage of enforcement vessels, which to some extent has allowed IUU activities conducted by foreign nationals. MMEA currently has 70 vessels and 190 boats nationwide, but most of them were obsolete and not functioning well.[43] MMEA was scheduled to have received at least one OPV in September 2022, after the government had previously given an 18-month extension to TH Heavy Engineering to complete all three vessels.[44] The first of the three OPVs was not delivered until October 2022. Meanwhile, the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) has taken an increasingly active role in fisheries law enforcement. On July 23, 2022, with a close connection through advanced information technology and interagency communication, RMN’s KD Admiral Hang Nadim carried out the expulsion of foreign fishing boats until exiting the border of the country’s waters.[45] On 17 October, 2022,RMN’s KD Pendekar detained a Vietnamese fishing boat with 15 crews.[46] In addition, the Malaysian armed forces and the law enforcement agency attach importance to coordination. On 22 March, 2023, MMEA’s patrol ship KM Jujur intercepted two Vietnamese fishing boats as a result of information channelled by a Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) maritime patrol aircraft team.[47]

The Vietnamese fishing boats’ IUU fishing activities are even more rampant in the northern part of the South China Sea. As South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI)’s map on fishing vessels revealed, thousands of Vietnamese fishing boats are present in the territorial sea and the internal waters of China’s Hainan Island, Guangxi and Guangdong in 2022. The IUU fishing poses threats and challenges to maritime cooperation, fishery resources conservation and security of neighboring countries in the South China Sea. There is still a long way to achieve fisheries resources preservation and conflict management in the SCS.

In the first 10 months of 2022, Vietnam profited $9.5 billion from fisheries exports, up 34 percent from the same period last year. In October 2017, the European Union (EU) issued a “yellow card” warning against Vietnam’s persistent fishing violations. In order to lift the card, the Vietnamese government has introduced a series of rectification measures, but the implementation is still a problem. In 2018 and 2019, European Commission (EC) delegation conducted on-site inspections on Vietnam’s efforts in combating illegal fishing. Recommendations were put forward to rectify the insufficient implementation. Constrained by the pandemic, the EC inspection team did not visit Vietnam again until the end of October 2022. Meanwhile, preventing Vietnamese local fishing boats from illegally fishing in other countries’ waters was again proposed by the EU officials after the inspection. The EC mission said it will continue with inspection and assessment in Vietnam in another six months before deciding whether to revoke the “yellow card”. [48]

Overall, the Vietnamese government has taken steps to tackle IUU fishing in the SCS, but the results is modest. The sustainable development of marine fishery resources in the SCS concerns the vital interests of coastal states and fishermen. The Vietnamese government needs to continuously face up to the IUU fishing problem, taking effective measures to strengthen its fishery management, raising fishermen’s law-abiding awareness, enhancing the ability to inspect, control and supervise illegal fishing activities, and fulfilling corresponding international obligations.