In China’s surrounding waters, including the South and East China Seas, despite the growing competition as well as sea and air encounters between the two militaries, it warrants highlighting that most of the encounters, more than ten times per day and thousands of times every year, are safe and professional.

For instance, the U.S. 7th Fleet spokesperson LT Mark Langford said in an emailed statement on the recent U.S. Navy Taiwan Strait transit that “all interactions with foreign military forces during the transit were consistent with international standards and practices and did not impact the operation.” Rear Adm. J.T. Anderson, Carrier Strike Group 3 commander, said in a 3rd Fleet August news release “We were operating in the vicinity [of] Chinese warships at times, mostly … that shadowed our ship,” she said, noting, “It was safe and professional the entire time that we interacted with them. During some flight operations, our aircraft did interact with some of their aircraft, but again it remained safe and professional every time we interacted with them.”

The desire to avoid direct military conflict has been unmistakably expressed at the top levels of both countries and militaries. Despite the suspension of formal channels of communication between the two militaries like MMCA, there are still open channels of communication between the front-line commanders, for example The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 (COLREGS) and The Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES). In general, the situation is not as grim as the media and some scholars make it out to be.

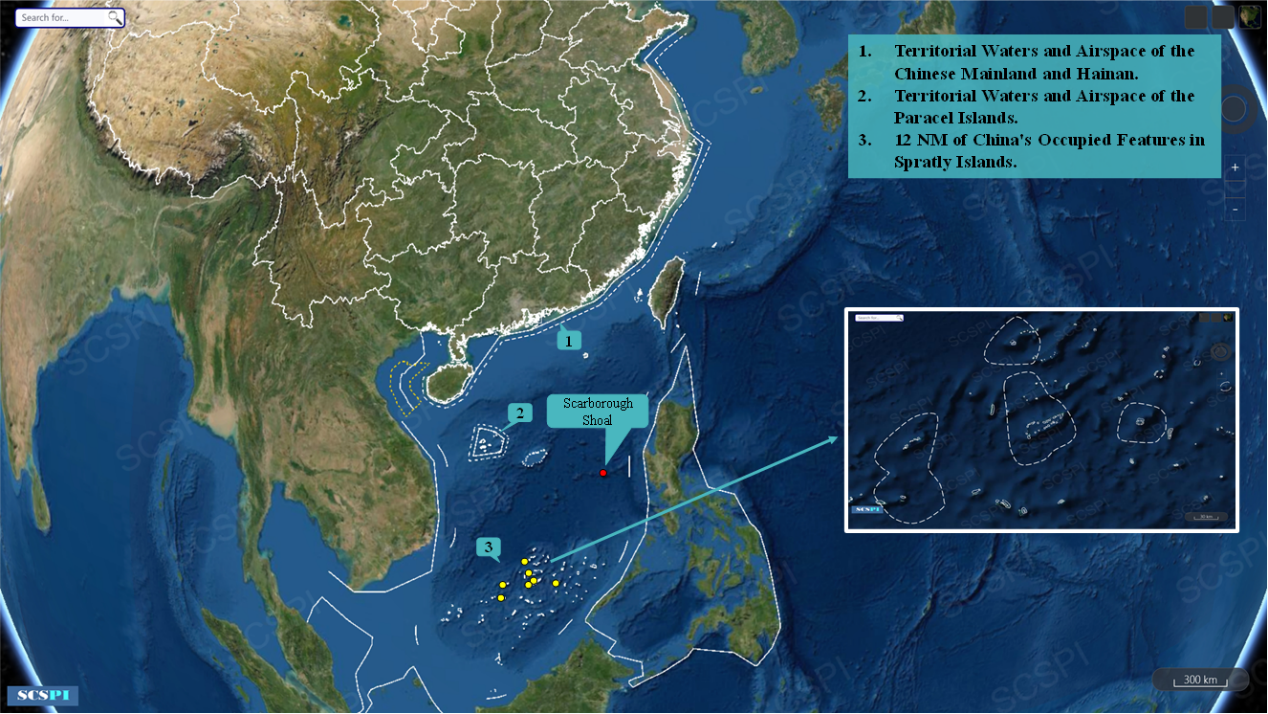

Nonetheless, in some places and circumstances, the risk is really high. When China and the US talk about military encounters and exchange criticism, firstly, we should know where these encounters occurred. Different regions have different legal and political meanings for both sides. Most confrontational encounters between two militaries happen in the following four situations:

1. U.S. forces approach the territorial waters and airspace of the Chinese Mainland and Hainan then the PLA responds, sometimes, resulting in, the warships or aircraft of the two sides operating in very close proximity.

2. U.S. forces enter the territorial waters and airspace of the Paracel Islands to conduct freedom of navigation operations, and the PLA warns them to leave.

3. U.S. forces enter within 12 nautical miles of China's occupied features in the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal to conduct freedom of navigation operations, and the PLA warns them to leave. On September 30, 2018, USS Decatur (DDG-73) had an unusual close encounter (link is external) with the Chinese destroyer Lanzhou (170), just 40 meters away, in the vicinity of Gaven Reef in the South China Sea.

4. Both sides conduct close reconnaissance on the other’s military operations, including live-fire drills of the other side. Sometimes, it is too close and too dangerous. Esp, when PLA conducts live-fire drills, the U.S. military usually pays little attention to traffic warnings and just enters. In August 2020, a U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft trespassed into airspace used for live-fire exercises by the Northern Theater Command of the People's Liberation Army.

China’s reasonable concerns on U.S. military operations in its surrounding waters

China does not have the ability or serious intention to drive U.S. forces out of the Western Pacific, including the South China Sea. For China, coexistence is a rational choice. Of course, China is unhappy with the U.S. military operations in its surrounding waters. However, in most areas and cases, the Chinese military follows and monitors the situation based on international practice, which has not any different from how the US and Japan respond to Chinese military forces operating in their surrounding waters. Only in the four categories of encounters above, China often responds in a more forthright manner. Strategically, China opposes that the U.S. constantly challenging its sovereignty of the features and national security; Technically or operationally, China opposes that the U.S. operations endanger the safety of personnel onshore or offshore. Put strategic and legal disagreements aside from a Chinese perspective. There are three reasonable concerns:

1. Some U.S. reconnaissance sorties are too close and aggressive. On September 4, 2021, an RC-135S Cobra Ball ballistic missile-detection reconnaissance aircraft came close to Jiaozhou Bay of Shandong Province for close-in reconnaissance, with the nearest point less than 20 nautical miles from China’s territorial sea baseline. On November 29, a P-8A antisubmarine aircraft transited the Taiwan Strait, during which it once came around 15.91 nautical miles from China’s territorial sea baseline.

2. Worries about frequent U.S. military accidents. In recent years, the high operational tempo of US forces, and resultant impacts on training and proficiency, have resulted in unfortunate accidents (such as that involving the USS Fitzgerald in 2017). With US and Chinese forces operating in close proximity, the potential of an inadvertent accident occurring cannot be dismissed.

3. Publicity surrounding and political manipulation of military operations and encounters. Military operations, of course, have political implications. However, in recent years, the United States has attached military operations with greater political and diplomatic weight. FONOPs in the 12 miles of China’s occupied features and Taiwan Strait Transit are the most representative. Whilst the US undertook FONOPS in the South China Sea before the USS Lassen’s 2015 FONOP in the waters around the Spratly Islands, it has subsequently undertaken such FONOPS with a greater degree of transparency and public profile than previously. This is also the case with the Taiwan Strait Transits. Since 2018, after every transit, the US Navy always has made an announcement or spoken anonymously to the media through officials, deliberately creating public opinion.