“The United States cannot accept less than the cessation in full right and sovereignty of the island of Luzon. It is desirable, however, that the United States shall acquire the right of entry for vessels and merchandise belonging to citizens of the United States into such ports of the Philippines as are not ceded to the United States upon terms of equal favor with Spanish ships and merchandise.”

Papers Relating to the Treaty with Spain, 30th January 1899

“Spain ceded to the United States the archipelago known as the Philippine Islands, and comprehending the islands lying within the following line...”[1]

——Article III, Treaty of Peace between the United States and Spain, 1898.

Introduction

Recently, the war of words that continues to create volumes for followers of the South China Sea dispute has been taken in a new direction, although the issues of the past remain, perpetuating a north-south divide based on religious and other differences because the US did not want the entire archipelago. An architect of a widely accepted Phillipines public perception today, Justice Antonio T. Carpio, wrote recently of the potential for an International Court of Justice ‘ICJ’ binding voluntary arbitration that should involve all parties to what he called the territorial dispute. Citing a historic source from 1734, it is claimed that the Philippines has: “The oldest documentary evidence of sovereignty over the Spratlys.”[2] From the wording of the opinion piece, it might be thought this was a new finding, however Justice Carpio was aware of the Murillo Velarde map in October 2018, when three examples were shown to the Manila section of the 36th International Symposium of the International Map Collectors Society that he attended.[3] This view builds on an earlier eBook; The South China Sea Dispute: Philippine Sovereign Rights and Jurisdiction in the West Philippine Sea, which also utilised inaccurate map reading in an attempt to attribute sovereign claims.[4] Utilising texts and other information of public notoriety in a wide-ranging study of the Philippines from legal and historical standpoints, this series of articles challenges that view, and additional claims that this map attributes any Spratly Islands sovereignty rights to the Philippines via the 1898 Treaty of Paris or its later clarifications with Spain, Holland, and Great Britain in 1900, 1928, and 1930.[5] In addition, it considers aspects of Phillipines territorial waters claims through US Colonial era laws, which exhibit how the US thought of the imaginary lines in the 1898 Treaty, following the description in Article III: “Comprehending the islands.”[6] In an era when the Phillipines were not politically or legally defined as supposed, this study finds the basis for dispute that is claimed by Justice Carpio falls to the ground.

The study is separated into four parts, each with their own distinct approaches and eras. There are the historical claims made to the 2016 Tribunal in Philippines v China, ‘The 2016 Tribunal Issue’. Claims made by Justice Carpio in May 2021 concerning the relevance of a 1734 map, the Murillo Velarde, which reflect on the Philippines actual territory, as defined one hundred and sixty-four years after the map was drawn and continued through the maritime laws enacted in the Philippine Legislature, ‘Philippines Territorial ‘Rights’, Treaties, and the 1935 Constitution’. The period in the 1930-40’s when Japan expansion into the Spratly Islands took place on a large scale, and independence was of primary interest, a development interrupted by the Second World War, ‘Japanese expansion in the Spratly Islands and Independence’. A historical view, before the 1898 Spanish-American War when Spain formed the Philippines into an entity on paper that the US accepted, even though neither State was to be in physical control of the archipelago until the 20th century, and then only tenuously; ‘The Formation of the Philippines’. Finally, ‘The Findings of Surveyors’ examines the public navigational record, information detailed in Directories and Pilots used to navigate the seas, primarily those created by the East India Company, the Royal Navy, and later, the US Navy, when it began to create its own records, rather than rely on data collected by others, primarily the East India Company and Royal Navy. Overall, this cross disciplinary approach, focused primarily on history, law, and international relations, provides a view of the Philippines that does not match todays perception.

Justice Carpio has separated the South China Sea dispute into two distinct areas, which is part of a strategy that has been undertaken in the wrong order for an equitable result. In an opinion piece published recently by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, Justice Carpio stated:

There are two kinds of dispute in the Spratlys, the territorial dispute and the maritime dispute. The territorial dispute involves the issue of sovereignty over the geologic features above water at high tide and their surrounding territorial seas. The maritime dispute involves the economic right to exploit the resources in the waters and seabed beyond the territorial seas....

The Philippines should initiate now the Spratlys Arbitration because, like in the South China Sea Arbitration, the Philippines has a very strong case.

First, the Philippines has the oldest documentary evidence of sovereignty over the Spratlys—the 1734 Murillo Velarde map showing that the official territory of the Philippines during the Spanish colonial regime included the Spratlys, then called Los Bajos de Paragua. There is no older map from China, Vietnam, Malaysia, or from any other country, showing that the Spratlys formed part of their territory.[7]

However, in 2016, Justice Carpio stated to ASB-CBN News, another Filipino news channel: “Reed Bank is off Palawan but it is not part the Spratlys anymore.”[8] There is no mention of the Philippines so-called ‘Kalayaan Islands’, which the Philippines Government claimed were distinct in 2011, in response to a 7th May 2009 Chinese statement.[9] The Spratly Islands, the islands known in hydrographic circles as part of the Dangerous Ground that contains islands, reefs, banks, and other features, is the name which identifies the entire archipelago in public perceptions.[10] This is visible in Justice Carpio’s 2016 statement, which exhibits the ordinary meaning of the Spratly Islands as a geographic entity.[11] The problem with this perception is that the two issues have become inseparable, in part because of changing Filipino views and claims regarding its territory and waters, leading to the statement that Reed Bank is not part of the Spratly’s any more is a bid to separate the bank from the territorial question.[12] Instead of the view from the land, which in Western perceptions dominates the sea, that could have been considered first and settled multiple sovereignty claims, the strategy behind the initial Phillipines approach under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ‘UNCLOS’, which relied in part on a carefully crafted narrative, was to create a perception that the whole issue was settled if the Philippines prevailed, rather than a small part of the maritime problem.

A major reason for the dispute is the question of oil and gas reserves, an area of great interest for the Philippines after independence was gained in 1946. Rodolfo Severino notes:

In 1949, the Philippines had laid claim to petroleum and natural gas in ‘submerged lands within the territorial waters or on the continental shelf, ...seaward from the shores of the Philippines which are not within the territories of other countries,’ as belonging to the state.[13]

The Philippines question of sovereignty over the Spratly Islands is in part due to the potential for fuel resources, an issue began to arise in the 1930’s. Justice Carpio’s purpose has in part an attempt to achieve Philippines domination in the region to its West with this aim in mind, creating a public perception through the utilisation of old maps of questionable accuracy is a part of the strategy, leading to claims that other States may be ‘stealing’ resources.

This narrative can be challenged on three grounds. First, claims brought before the 2016 Tribunal initiated under the UNCLOS and the findings that resulted from them, showing there was a narrative that ignored recorded and well known history.[14] Second, claims to attribute Phillipines sovereign rights to a 1734 Spanish map, known as the Murillo Velarde, drawn before Spain was ceded the island of Palawan by the Sultan of Brunei, followed by its initial Spanish occupation on 30th April 1753.[15] Third, the findings of independent sources, which the Tribunal relied upon in making its Award, that present a completely different narrative, based on historical information recorded by two organised States, the United Kingdom of Great Britain, and the United States of America. The results given by these three grounds finds that Justice Carpio is incorrect in his claims of historical Philippine territorial integrity, continuity, or the status of the islands and waters surrounding the Philippines, and in the South China Sea.

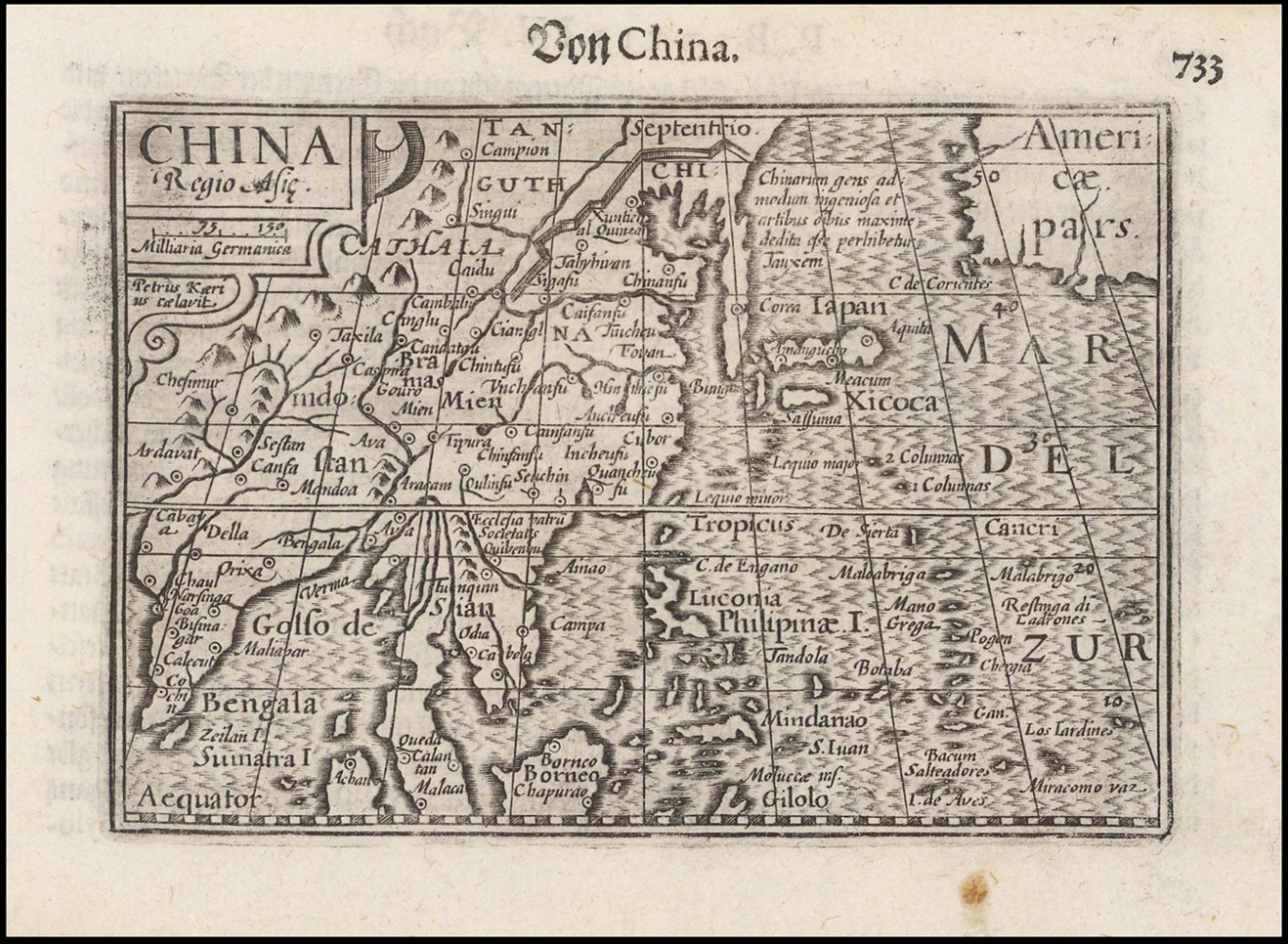

China Regio Asie (1612).[16]